In part 1 of “The Evolving Story of Instructional Coaching: A Summary of Our Research”, I summarized how my colleagues and I came to a preliminary understanding of instructional coaching. This post continues the discussion of the evolution of our work into what it is now.

Irma Brasseur-Hock – my colleague on the project – and I knew that teacher support would be important, but we didn’t know what it would look like. We experimented with different kinds of collaboration, and in an article from 1998, I described “learning consultants” – an early term for what later became “instructional coaches.” I described these professionals as “part coach and part anthropologist,” adding that their “main task is to help teachers see how research-validated practices offer useful solutions to the problems they face” and make it easier for them to implement them.

Then, in 1999, funding from the U.S. Department of Education GEAR UP program (a grant designed to increase the number of low-income students prepared to enter and succeed in postsecondary education) enabled us to study onsite intensive professional development for a decade.

While I was conducting that research, my colleague Don Deshler made the important observation that the term “consultant” suggests an unequal power dynamic between professional developer and teacher, so I started using the term “instructional collaborator” instead of “learning consultant.” During the GEAR UP study, I finally arrived at the term “instructional coach” three years later, again at Don’s suggestion for refinement.

No model for anything similar existed at that time, so my colleagues and I developed and refined an instructional coaching model. Although our early, informal studies may have lacked rigor, they nevertheless laid the foundation for what I believe was the first major article about instructional coaching (Knight, 2004) and, later, the first extended book on the topic, Instructional Coaching: A Partnership Approach to Improving Instruction (Knight,2007).

While my colleagues and I had made revelatory discoveries through our research and developed the first model for instructional coaching, there was plenty of more rigorous research ahead.

That research continued in 2009, when my colleague Jake Cornett and I completed a more rigorous study of instructional coaching, in which 51 middle school teachers attended an after-school workshop on an inclusive planning and teaching strategy, The Unit Organizer (Lenz et al.,1993).

Observations showed that, compared to their colleagues who did not attend the workshop, teachers who received coaching were more likely to implement (87% vs. 33%) and taught with closer fidelity to the original model. Further, more coached than non-coached teachers told us that they continued to use the teaching routine (68% vs. 18%); and coached teachers also told us they would be more likely to use the teaching routine in the future (96% vs. 35%).

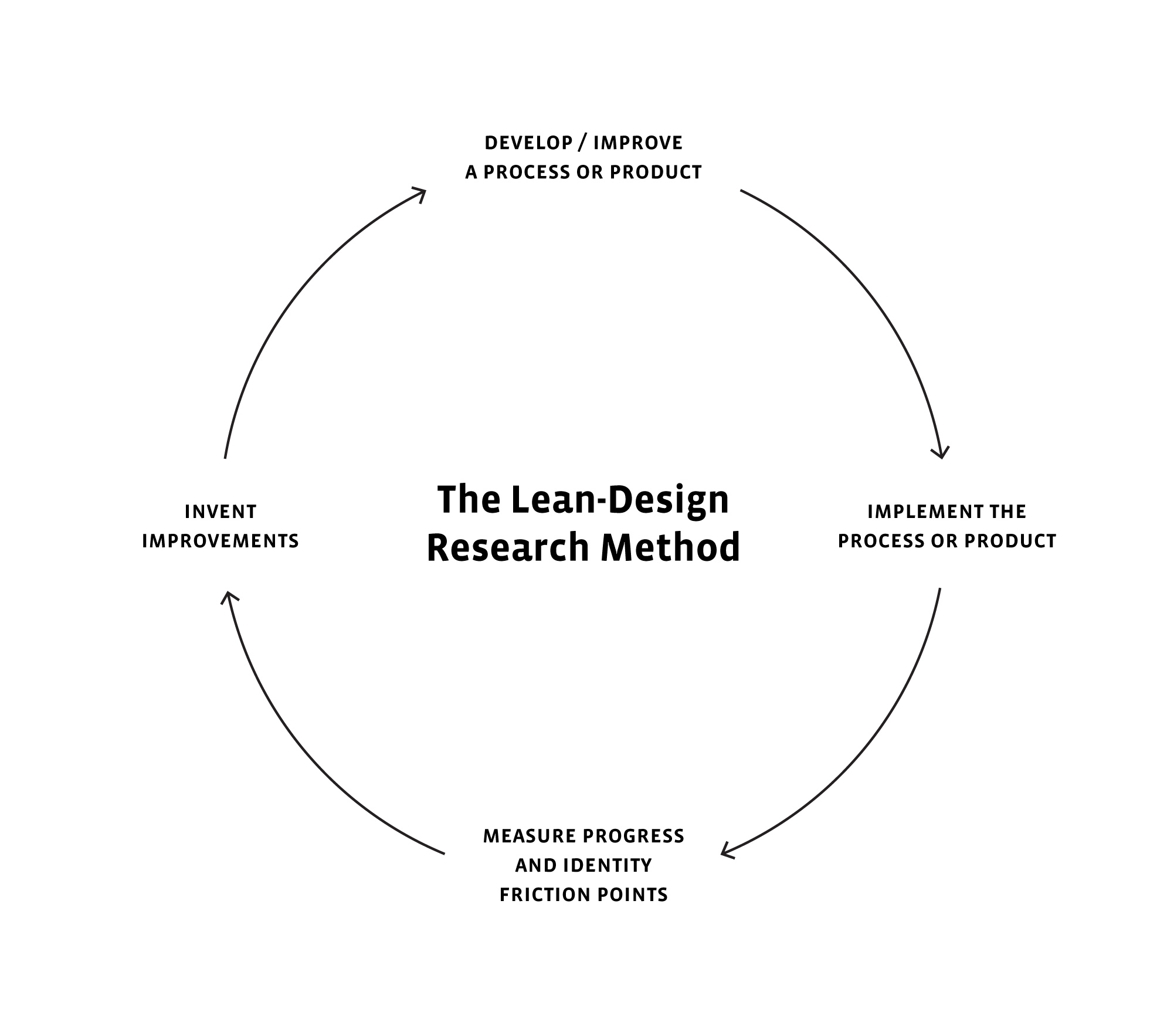

Coached by an expert on design research at the University of Kansas, Barbara Bradley, my colleagues and I at the Kansas Coaching Project utilized design research (Bradley et al., 2013) to improve and refine our original instructional coaching model. These improvements, combined with the lean-research methods popularized by Eric Ries in The Lean Startup (2011), led to what I refer to as “lean-design research” in The Impact Cycle (Knight, 2018).

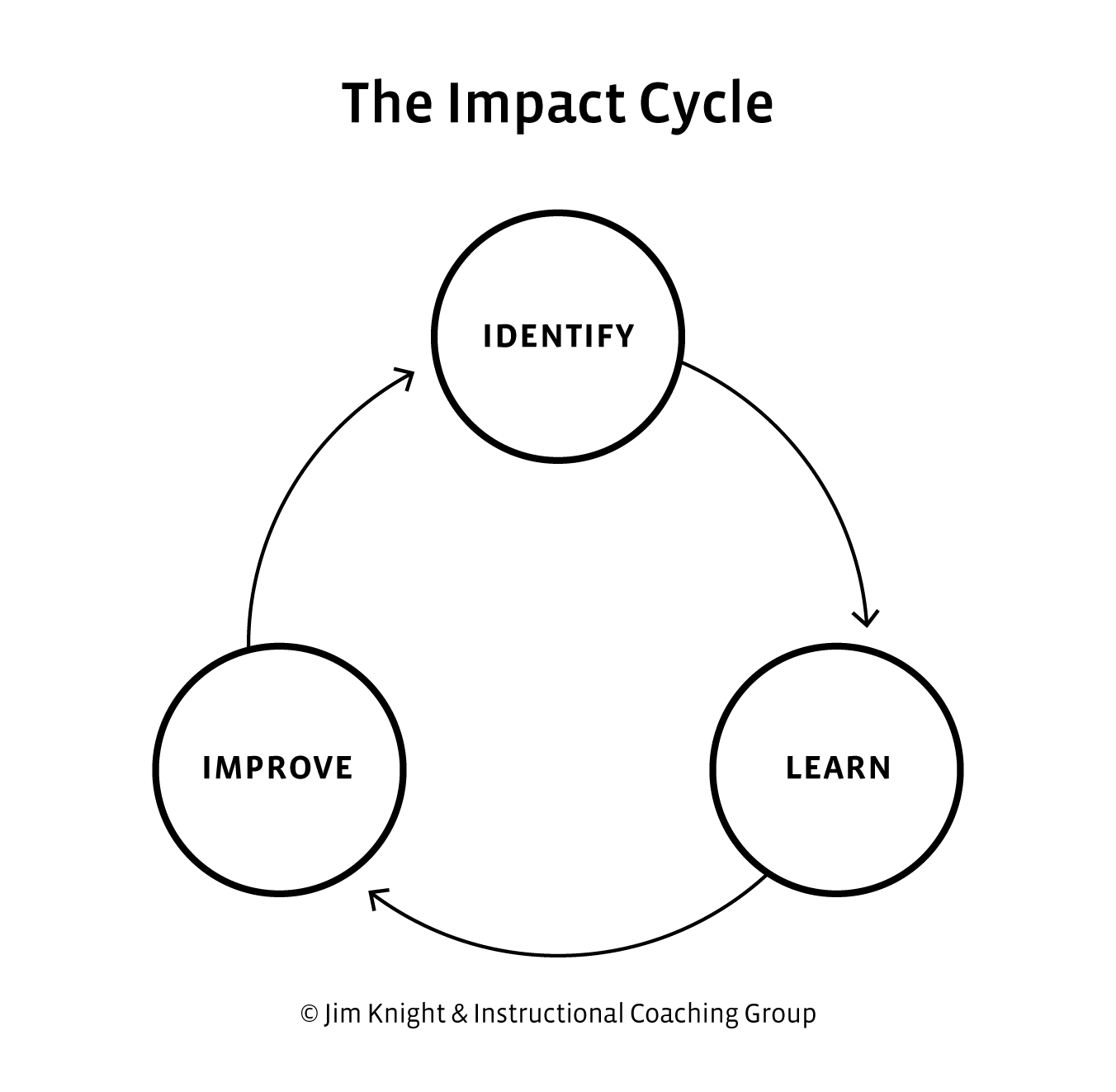

The refinements included:

- coaches and teachers using video to get a clear picture of reality

- a revised model for goal setting (PEERS goals)

- identification of a bank of powerful coaching questions

- identification of questioning skills

- more effective ways to demonstrate teaching strategies

- a streamlined, clearly defined coaching cycle: The Impact Cycle

Led by David Knight, a graduate student at The University of Kansas, my colleagues and I also conducted a multiple-baseline study to measure the impact of coaching on teaching and student engagement (Knight,2019). Again, observation data showed that teachers used significantly more targeted teaching practices after they had been coached than before. Additionally, measures of student engagement showed significant gains in time-on-task behavior after coaching (d = 1.03).

Over the past two decades, we have conducted many other research projects, including a review of the research literature (Knight, 2008) and a study of the characteristics of effective coaches (Knight, 2010). Together, the studies described here and in various books related to instructional coaching have led to the articulation of a simple and powerful model for instructional coaching.

More recently, I’ve written about how those being coached can become better professional learners (Knight, 2018), about the role of autonomy within coaching (Knight, 2019), and the importance of putting student engagement (along with student achievement) at the heart of instructional coaching (Knight, 2019).

Our research continues today so we can continue to learn and improve how best to support all educators because above all, ICG remains dedicated to creating professional development for coaches, teachers, and leaders so students experience better learning, better lives.