Teachers make between 800 and 1,500 decisions a day. With the constant bombardment of students’ personal and learning needs (plus unexpected early dismissals, server problems, and parent calls), teachers often feel as though they live continually in the moment, bouncing from one metaphorical fire drill to another.

This “pressure cooker” feeling is a key factor in teacher resistance to professional development. “You expect me to sit here for an hour to listen to a new reading approach when I have 15 grades due tomorrow in PowerSchool on the old approach? Seriously?” This difficulty in seeing beyond the issue of the moment is typically not intentional negativity or sabotage; rather, it is a sign of the cognitive overload of an extraordinarily stressful job.

If we want meaningful change in instruction, the ability to reflect is critical. In the latest video clip on the Partnership Principles, Jim Knight examines the necessity of reflection in both partnership relationships and in change. When we take the time to look back at what we have done in the past, look at what we are doing now, and look ahead to the changes we hope to see in the future, we make better, more deliberate decisions. We understand our own path and how to navigate barriers that may loom ahead. But amid all of the daily pressures of teaching, reflection can feel like a luxury.

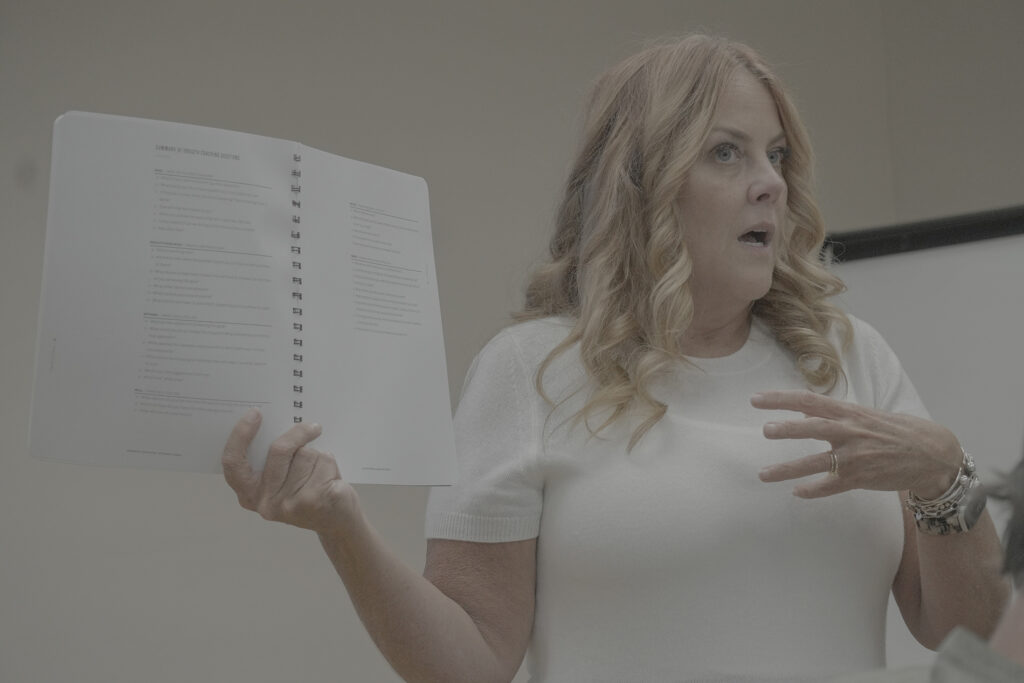

One of the strengths of instructional coaching as professional learning is the ability of the coach to prompt reflection through conversation. In helping the teacher to think through the goals and strategies they want to work on, the coach examines various aspects of the classroom in partnership with the teacher. When the teacher is overwhelmed by a million competing demands, the coach can help the teacher to move beyond those stresses and into a plan of action.

The first time I worked with an instructional coach, perhaps the most valuable part of those interactions was Sherry compelling me to reflect merely by asking me questions. “What has this looked like with students you’ve taught before? Describe what students are doing now and what concerns you about that. What would you like to see students doing instead?” Because that problem concerned student behavior, I was flustered and emotional, wondering why my old “schtick” wasn’t working. Sherry helped me to move into a more logical and problem-solving mindset by helping me to place student behaviors in context and to be clear about what I wanted. That reflection helped me to move forward in a student-focused way, not a “These kids are driving me crazy!” way.

Margaret Wheatley said, “Without reflection, we go blindly on our way, creating more unintended consequences, and failing to achieve anything useful.” The feeling of moving from crisis to crisis, troubleshooting from moment to moment, can give one a false sense of adrenaline-fueled competence: “I handled it all!” But it also gives us a lingering case of myopia, the perception that the only thing that matters is the thing in front of us, not the big picture. Reflection is the key to long-term change because it forces a focus on that big picture, beyond the fire drills, beyond the bombardment.